5

Oil paintings often depict things. Things which in reality are buyable. To have a thing painted and put on a canvas is not unlike buying it and putting it in your house. If you buy a painting you buy also the look of the thing it represents.

This analogy between possessing and the way of seeing which is incorporated in oil painting, is a factor usually ignored by art experts and historians. Significantly enough it is an anthropologist who has come closest to recognizing it.

Levi-Strauss writes:

It is this avid and ambitious desire to take possession of the object for the benefit of the owner or even of the spectator which seems to me to constitute one of the outstandingly original features of the art of Western civilization.

If this is true - though the historical span of Levi-Strauss's generalization may be too large - the tendency reached its peak during the period of the traditional oil painting.

The term oil painting refers to more than a technique. It defines an art form. The technique of mixing pigments with oil had existed since the ancient world. But the oil painting as an art form was not born until there was a need to develop and perfect this technique (which soon involved using canvas instead of wooden panels) in order to express a particular view of life for which the techniques of tempera or fresco were inadequate. When oil paint was first used - at the beginning of the fifteenth century in Northern Europe - for painting pictures of a new character, this character was somewhat inhibited by the survival of various medieval artistic conventions. The oil painting did not fully establish its own norms, its own way of seeing, until the sixteenth century.

Nor can the end of the period of the oil painting be dated exactly. Oil paintings are still being painted today. Yet the basis of its traditional way of seeing was undermined by Impressionism and overthrown by Cubism. At about the same time the photograph took the place of the oil painting as the principal source of visual imagery. For these reasons the period of the traditional oil painting may be roughly set as between 1500 and 1900.

The tradition, however, still forms many of our cultural assumptions. It defines what we mean by pictorial likeness. Its norms still affect the way we see such subjects as landscape, women, food, dignitaries, mythology. It supplies us with our archetypes of 'artistic genius'. And the history of the tradition, as it is usually taught, teaches us that art prospers if enough individuals in society have a love of art.

What is a love of art?

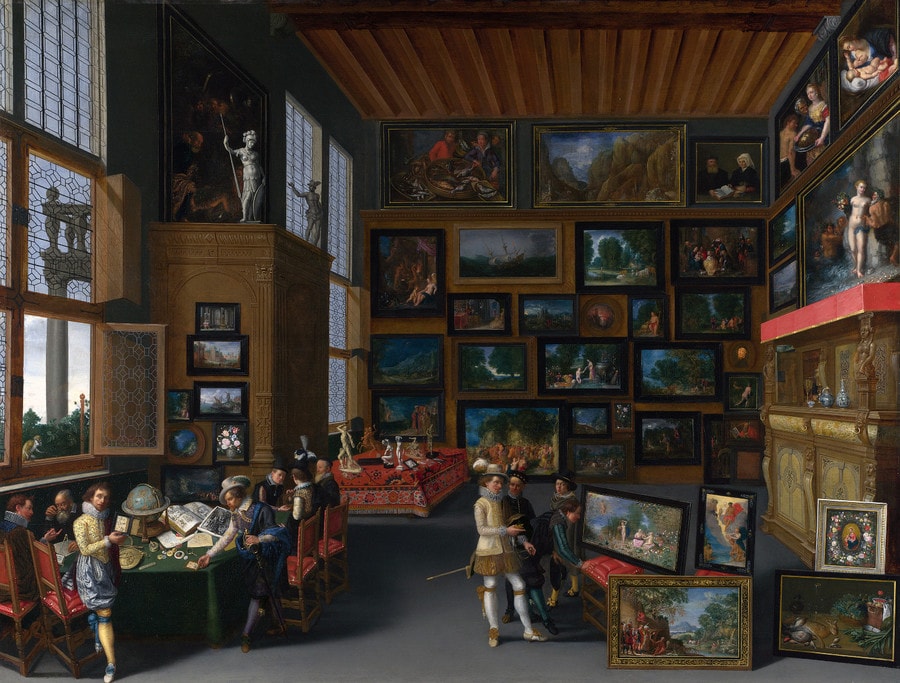

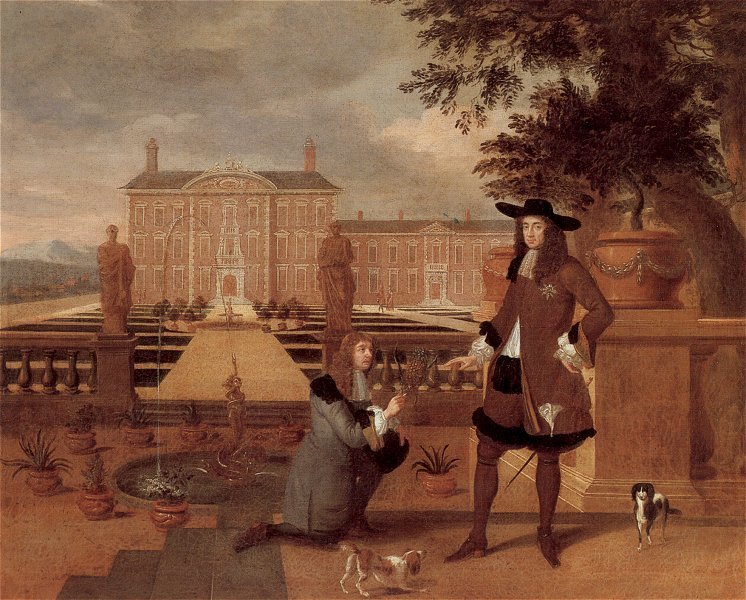

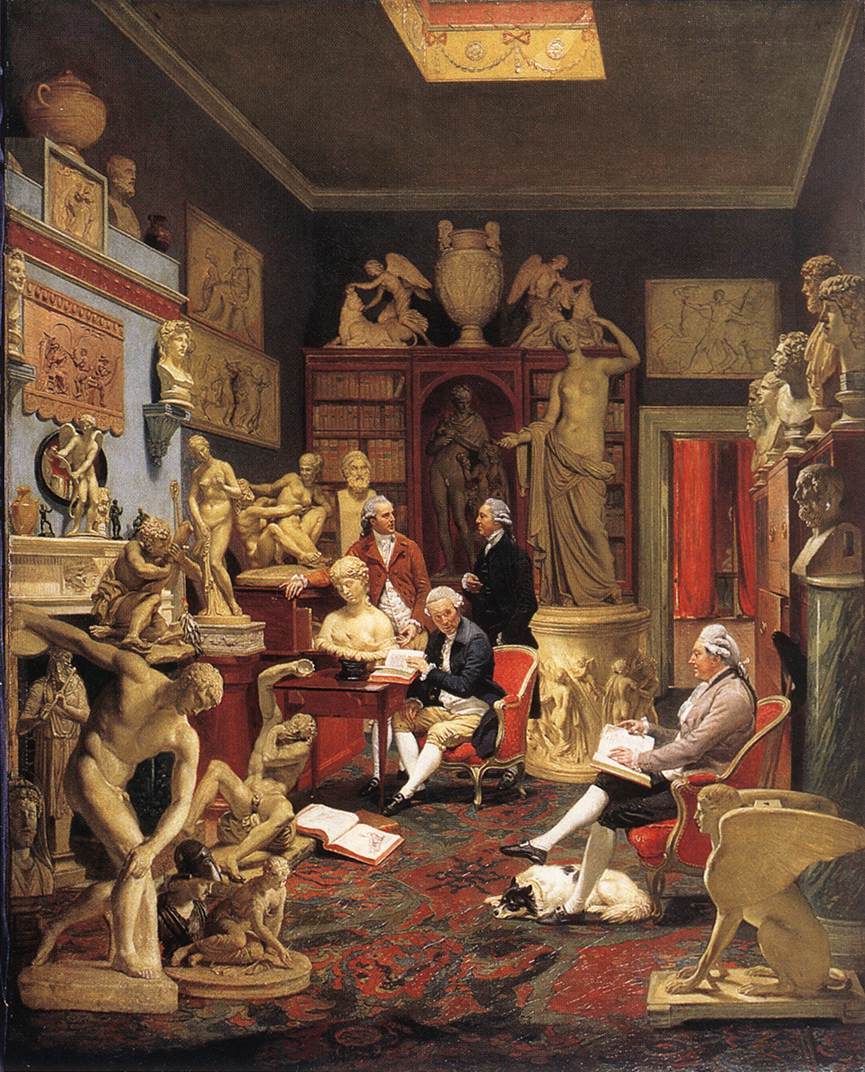

Let us consider a painting which belongs to the tradition whose subject is an art lover.

What does it show?

The sort of man in the seventeenth century for whom painters painted their paintings.

What are these paintings?

Before they are anything else, they are themselves objects which can be bought and owned. Unique objects. A patron cannot be surrounded by music or poems in the same WaY as he is surrounded by his pictures.

It is as though the collector lives in a house built of paintings. What is their advantage over walls of stone or wood?

The show him sights: sights of what he may possess.

Again, Levi-Strauss comments on how a collection of paintings can confirm the pride and amour-propre of the collector.

For Renaissance artists, painting was perhaps an instrument of knowledge but it was also an instrument of possession, and we must not forget, when we are dealing with Renaissance painting, that it was only possible because of the immense fortunes which were being amassed in Florence and elsewhere, and that rich Italian merchants looked upon painters as agents, who allowed them to confirm their possession of all that was beautiful and desirable in the world. The pictures in a Florentine palace represented a kind of microcosm in which the proprietor, thanks to his artists, had recreated within easy reach and in as real a form as possible, all those features of the world to which he was attached.

The art of any period tends to serve the ideological interests of the ruling class. If we were simply saying that European art between 1500 and 1900 served the interests of the successive ruling classes, all of whom depended in different ways on the new power of capital, we should not be saying anything very new. What is being proposed is a little more precise; that a way of seeing the world, which was ultimately determined by new attitudes to property and exchange, found its visual expression in the oil painting, and could not have found it in any other visual art form.

Oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects. Everything became exchangeable because everything became a commodity. All reality was mechanically measured by its materiality. The soul, thanks to the Cartesian system, was saved in a category apart. A painting could speak to the soul - by way of what it referred to, but never by the way it envisaged. Oil painting conveyed a vision of total exteriority.

Pictures immediately spring to mind to contradict this assertion. Works by Rembrandt, El Greco, Giorgione, Vermeer, Turner, etc. Yet if one studies these works in relation to the tradition as a whole, one discovers that they Were exceptions of a very special kind.

The tradition consisted of many hundreds of thousands of canvases and easel pictures distributed throughout Europe. A great number have not survived. Of those which have survived only a small fraction are seriously treated today as works of fine art, and of this fraction another small fraction comprises the actual pictures repeatedly reproduced and presented as the work of 'the masters'.

Visitors to art museums are often overwhelmed by the number of works on display, and by what they take to be their own culpable inability to concentrate on more than a few of these works. In fact such a reaction is altogether reasonable. Art history has totally failed to come to terms with the problem of the relationship between the outstanding work and the average work of the European tradition. The notion of Genius is not in itself an adequate answer. Consequently the confusion remains on the walls of the galleries. Third-rate works surround an outstanding work without any recognition - let alone explanation - of what fundamentally differentiates them.

The art of any culture will show a wide differential of talent. But in no other culture is the difference between 'masterpiece' and average work so large as in the tradition of the oil painting. In this tradition the difference is not just a question of skill or imagination, but also of morale. The average work - and increasingly after the seventeenth century - was a work produced more or less cynically: that is to say the values it was nominally expressing were less meaningful to the painter than the finishing of the commission or the selling of his product. Hack work is not the result of either clumsiness or provincialism; it is the result of the market making more insistent demands than the art. The period of the oil painting corresponds with the rise of the open art market. And it is in this contradiction between art and market that the explanations must be sought for what amounts to the contrast, the antagonism existing between the exceptional work and the average.

Whilst acknowledging the existence of the exceptional works, to which we shall return later, let us first look broadly at the tradition.

What distinguishes oil painting from any other form of painting is its special ability to render the tangibility, the texture, the lustre, the solidity of what it depicts. It defines the real as that which you can put your hands on.

Although it's painted images are two-dimensional, its potential of illusionism is far greater than that of sculpture, for it can suggest objects possessing colour, texture and temperature, filling a space and, by implication, filling the entire world.

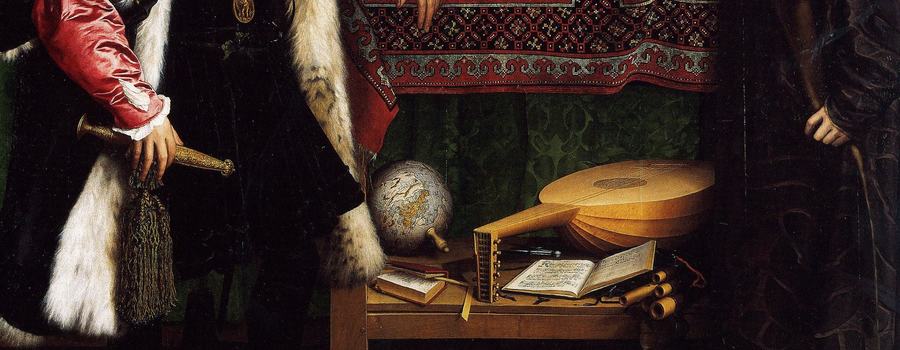

Holbein's painting of The Ambassadors (1533) stands at the beginning of the tradition and, as often happens with a work at the opening of a new period, its character is undisguised. The way it is painted shows what it is about. How is it painted?

It is painted with great skill to create the illusion in the spectator that he is looking at real objects and materials. We pointed out in the first essay that the sense of touch was like a restricted, static sense of sight. Every square inch of the surface of this painting, whilst remaining purely visual, appeals to, importunes, the sense of touch. The eye moves from fur to silk to metal to wood to velvet to marble to paper to felt, and each time what the eye perceives is already translated, within the painting itself, into the language of tactile sensation. The two men have a certain presence and there are many objects which symbolize ideas, but it is the materials, the stuff, by which the men are surrounded and clothed which dominate the painting.

Except for the faces and hands, there is not a surface in this picture which does not make one aware of how it has been elaborately worked over - by weavers, embroiderers, carpet-makers, goldsmiths, leather workers, mosaic-makers, furriers, tailors, jewellers - and of how this working-over and the resulting richness of each surface has been finally worked-over and reproduced by Holbein the painter.

This emphasis and the skill that lay behind it was to remain a constant of the tradition of oil painting.

Works of art in earlier traditions celebrated wealth. But wealth was then a symbol of a fixed social or divine order. Oil painting celebrated a new kind of wealth - which was dynamic and which found its only sanction in the supreme buying power of money. Thus painting itself had to be able to demonstrate the desirability of what money could buy. And the visual desirability of what can be bought lies in its tangibility, in how it will reward the touch, the hand, of the owner.

In the foreground of Holbein's Ambassadors there is a mysterious, slanting, oval form. This represents; a highly distorted skull: a skull as it might be seen in a distorting mirror. There are several theories about how it was painted and why the ambassadors wanted it put there. But all agree that it was a kind of memento mori: a play on the medieval idea of using a skull as a continual reminder of the presence of death. What is significant for our argument is that the skull is painted in a (literally) quite different optic from everything else in the picture. If the skull had been painted like the rest, its metaphysical implication would have disappeared; it would have become an object like everything else, a mere part of a mere skeleton of a man who happened to be dead.

This was a problem which persisted throughout the tradition. When metaphysical symbols are introduced (and later there were painters who, for instance, introduced realistic skulls as symbols of death), their symbolism is usually made unconvincing or unnatural by the unequivocal, static materialism of the painting-method.

It is the same contradiction which makes the average religious painting of the tradition appear hypocritical. The claim of the theme is made empty by the way the subject is painted. The paint cannot free itself of its original propensity to procure the tangible for the immediate pleasure of the owner. Here, for example, are three paintings of Mary Magdalene.

The point of her story is that she so loved Christ that she repented of her past and came to accept the mortality of flesh and the immortality of the soul. Yet the way the pictures are painted contradicts the essence of this story. It is as though the transformation of her life brought about by her repentance has not taken place. The method of painting is incapable of making the renunciation she is meant to have made. She is painted as being, before she is anything else, a takeable and desirable woman. She is still the compliant object of the painting-method's seduction.

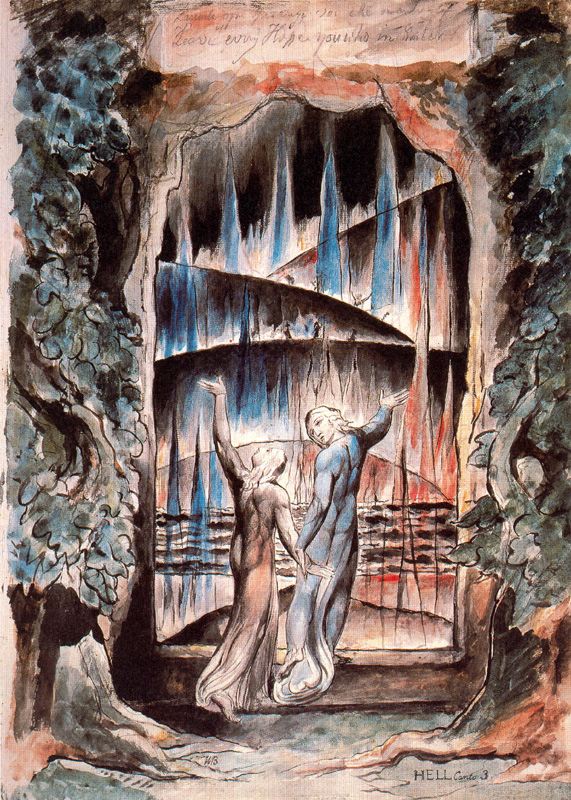

It is interesting to note here the exceptional case of William Blake. As a draughtsman and engraver Blake learnt according to the rules of the tradition. But when he came to make paintings, he very seldom used oil paint and, although he still relied upon the traditional conventions of drawing, he did everything he could to make his figures lose substance, to become transparent and indeterminate one from the other, to defy gravity, to be present but intangible, to glow without a definable surface, not to be reducible to objects

This wish of Blake's to transcend the 'substantiality' of oil paint derived from a deep insight into the meaning and limitations of the tradition.

Let us now return to the two ambassadors, to their presence as men. This will mean reading the painting differently: not at the level of what it shows within its frame, but at the level of what it refers to outside it.

The two men are confident and form al; as between each other they are relaxed. But how do they look at the painter - or at us ? There is in their gaze and their stance a curious lack of expectation of any recognition. It is as though in principle their worth cannot be recognized by others. They look as though they are looking at something of which they are not part. At something which surrounds them but from which they wish to exclude themselves. At the best it may be a crowd honouring them ; at the worst, intruders

What were the relations of such men with the rest of the world ?

The painted objects on the shelves between them were intended to supply - to the few who could read the allusions - a certain amount of information about their position in the world. Four centuries later we can interpret this information according to our own perspective.

The scientific instruments on the topshelf were for navigation. This was the time when the ocean trade routes were being opened up for the slave trade and for the traffic which was to siphon the riches from other continents into Europe, and later supply the capital for the take-off of the Industrial Revolution.

In 1519 Magellan had set out, with the backing of Charles V, to sail around the world. He and an astronomer friend, with whom he had planned the voyage, arranged with the Spanish court that they personally were to keep twenty percent of the profits made, and the right to run the government of any land they conquered.

The globe on the bottom shelf is a new one which charts this recent voyage of Magellan's. Holbein has added to the globe the name of the estate in France which belonged to the ambassador on the left. Beside the globe are a book of arithmetic, a hymn book and a lute. To colonize a land it was necessary to convert its people to Christianity and accounting, and thus to prove to them that European civilization was the most advanced in the world. Its art included.

The African kneels to hold up an oil painting to his faster. The painting depicts the castle above one of the Principal centres of the West African slave trade.

How directly or not the two ambassadors were involved in the first colonizing ventures is not particularly important, for what we are concerned with here is a stance towards the world; and this was general to a whole class. The two ambassadors belonged to a class who were convinced that the world was there to furnish their residence in it. In its extreme form this conviction was confirmed by the relations being set up between colonial conqueror and the colonized.

These relations between conqueror and colonized tended to be self-perpetuating. The sight of the other confirmed each in his inhuman estimate of himself. The circularity of the relationship can be seen in the following diagram - as also the mutual solitude. The way in which each sees the other confirms his own view of himself.

The gaze of the ambassadors is both aloof and wary. They expect no reciprocity. They wish the image of their presence to impress others with their vigilance and their distance. The presence of kings and emperors had once impressed in a similar way, but their images had been comparatively impersonal. What is new and disconcerting here is the individualized presence which needs to suggest distance. Individualism finally posits equality. Yet equality must be made inconceivable.

The conflict again emerges in the painting-method. The surface verisimilitude of oil painting tends to make the viewer assume that he is close to - within touching distance of - any object in the foreground of the picture. If the object is a person such proximity implies a certain intimacy.

Yet the painted public portrait must insist upon a formal distance. It is this - and not technical inability on the part of the painter - which makes the average portrait of the tradition appear stiff and rigid. The artificiality is deep within its own terms of seeing, because the subject has to be seen simultaneously from close-to and from afar. The analogy is with specimens under a microscope.

They are there in all their particularity and we can study them, but it is impossible to imagine them considering us in a similar way.

The formal portrait, as distinct from the self-portrait or the informal portrait of the painter's friend never resolved this problem. But as the tradition continued, the painting of the sitter's face became more and more generalized.

His features became the mask which went with the costume. Today the final stage of this development can be seen in the puppet tv appearance of the average politician.

Let us now briefly look at some of the genres of oil painting - categories of painting which were part of its tradition but exist in no other

Before the tradition of oil painting, medieval painters often used gold-leaf in their pictures. Later gold disappeared from paintings and was only used for their frames. Yet many oil paintings were themselves simple demonstrations of what gold or money could buy. Merchandise became the actual subject-matter of works of art.

Here the edible is made visible. Such a painting is a demonstration of more than the virtuosity of the artist. It confirms the owner's wealth and habitual style of living.

Paintings of animals. Not animals in their natural condition, but livestock whose pedigree is emphasized as a proof of their value, and whose pedigree emphasizes the social status of their owners. (Animals painted like pieces of furniture with four legs.)

Paintings of objects. Objects which, significantly enough, became known as objets d'art.

Paintings of buildings - buildings not considered as ideal works of architecture, as in the work of some early Renaissance artists - but buildings as a feature of landed property.

The highest category in oil painting was the history or mythological picture. A painting of Greek or ancient figures was automatically more highly esteemed than a still-life, a portrait or a landscape. Except for certain exceptional works in which the painter's own personal lyricism was expressed, these mythological paintings strike us today as the most vacuous of all. They are like tired tableaux in wax that won't melt. Yet their prestige and their emptiness were directly connected.

Until very recently - and in certain milieux even today - a certain moral value was ascribed to the study of the classics. This was because the classic texts, whatever their intrinsic worth, supplied the higher strata of the ruling class with a system of references for the forms of their own idealized behaviour. As well as poetry, logic and philosophy, the classics offered a system of etiquette. They offered examples of how the heightened moments of life - to be found in heroic action, the dignified exercise of power, passion, courageous death, the noble pursuit of pleasure - should be lived, or, at least, should be seen to be lived.

Yet why are these pictures so vacuous and so perfunctory in their evocation of the scenes they are meant to recreate? They did not need to stimulate the imagination. If they had, they would have served their purpose less well. Their purpose was not to transport their spectator-owners into new experience, but to embellish such experience as they already possessed. Before these canvases the spectator-owner hoped to see the classic face of his own passion or grief or generosity. The idealized appearances he found in the painting were an aid, a support, to his own view of himself. In those appearances he found the guise of his own (or his wife's or his daughters') nobility.

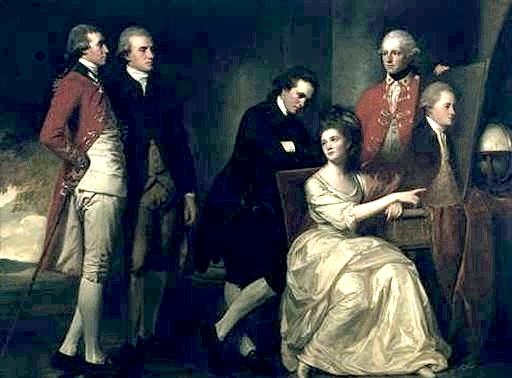

Sometimes the borrowing of the classic guise was simple, as in Reynolds's painting of the daughters of the family dressed up as Graces decorating Hymen.

Sometimes the whole mythological scene functions like a garment held out for the spectator-owner to put his arms into and wear. The fact that the scene is substantial, and yet, behind its substantiality, empty, facilitates the 'wearing' of it.

The so-called 'genre' picture - the picture of 'low life' - was thought of as the opposite of the mythological picture. It was vulgar instead of noble. The purpose of the 'genre' picture was to prove - either positively or negatively - that virtue in this world was rewarded by social and financial success. Thus, those who could afford to buy these pictures - cheap as they were - had their own virtue confirmed. Such pictures were particularly popular with the newly arrived bourgeoisie who identified themselves not with the characters painted but with the moral which the scene illustrated. Again, the faculty of oil paint to create the illusion of substantiality lent plausibility to a sentimental lie: namely that it was the honest and hard-working who prospered, and that the good-for-nothings deservedly had nothing.

Adriaen Brouwer was the only exceptional 'genre' painter. His pictures of cheap taverns and those who ended up in them, are painted with a bitter and direct realism which precludes sentimental moralizing. As a result his pictures were never bought - except by a few other painters such as Rembrandt and Rubens.

The average 'genre' painting - even when painted by a 'master' like Hals - was very different.

These people belong to the poor. The poor can be seen in the street outside or in the countryside. Pictures of the poor inside the house, however, are reassuring. Here the painted poor smile as they offer what they have for sale. (They smile showing their teeth, which the rich in pictures never do.) They smile at the better-off - to ingratiate themselves, but also at the prospect of a sale or a job. Such pictures assert two things: that the poor are happy, and that the better-o ff are a source of hope for the world.

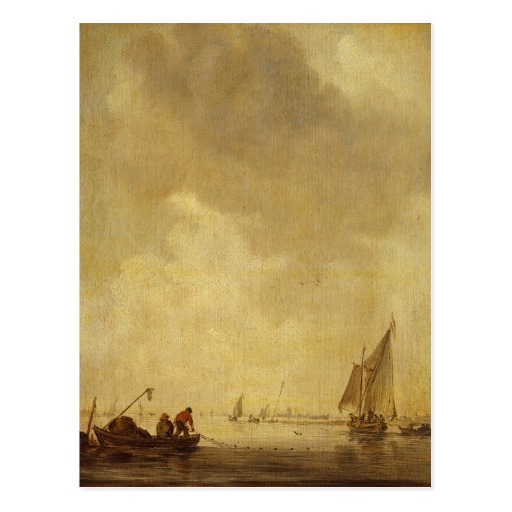

Landscape, of all the categories of oil painting, is the one to which our argument applies least.

Prior to the recent interest in ecology, nature was not thought of as the object of the activities of capitalism; rather it was thought of as the arena in which capitalism and social life and each individual life had its being. Aspects of nature were objects of scientific study, but nature-as-a-whole defied possession.

One might put this even more simply. The sky has no surface and is intangible; the sky cannot be turned into a thing or given a quantity. And landscape painting begins with the problem of painting sky and distance.

The first pure landscapes - painted in Holland in the seventeenth century - answered no direct social need. (As a result Ruysdael starved and Hobbema had to give up.) Landscape painting was, from its inception, a relatively independent activity. Its painters naturally inherited and so, to a large extent, were forced to continue the methods and norms of the tradition. But each time the tradition of oil painting was significantly modified, the first initiative came from landscape painting. From the seventeenth century onwards the exceptional innovators in terms of vision and therefore technique were Ruysdael, Rembrandt (the use of light in his later work derived from his landscape studies). Constable (in his sketches). Turner and, at the end of the period, Monet and the Impressionists. Furthermore, their innovations led Progressively away from the substantial and tangible tow ards the indeterminate and intangible

Nevertheless the special relation between oil painting and property did play a certain role even in the development of landscape painting. Consider the well-known example of Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews.

Kenneth Clark has written about Gainsborough and this canvas:

At the very beginning of his career his pleasure in what he saw inspired him to put into his pictures backgrounds as sensitively observed as the corn-field in which are seated Mr and Mrs Andrews. This enchanting work is painted with such love and mastery that we should have expected Gainsborough to go further in the same direction; but he gave up direct painting, and evolved the melodious style of picture-making by which he is best known. His recent biographers have thought that the business of portrait painting left him no time to make studies from nature, and they have quoted his famous letter about being 'sick of portraits and wishing to take his Viol de Gamba and walk off to some sweet village where he can paint landscips', to support the view that he would have been a naturalistic landscape painter if he had had the opportunity. But the Viol de Gamba letter is only part of Gainsborough's Rousseauism. His real opinions on the subject are contained in a letter to a patron who had been so simple as to ask him for a painting of his park: ' Mr Gainsborough presents his humble respects to Lord Hardwicke, and shall always think it an honour to be employed in anything for His Lordship; but with regard to real views from Nature in this country, he has never seen any place that affords a subject equal to the poorest imitations of Gaspar or Claude.'

Why did Lord Hardwicke want a picture of his park? Why did Mr and Mrs Andrews commission a portrait of themselves with a recognizable landscape of their own land as background?

They are not a couple in Nature as Rousseau imagined nature. They are landowners and their proprietary attitude towards what surrounds them is visible in their stance and their expressions.

Professor Lawrence Gowing has protested indignantly against the implication that Mr and Mrs Andrews were interested in property:

Before John Berger manages to interpose himself again between us and the visible meaning of a good picture, may I point out that there is evidence to confirm ihat Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews were doing something more with their stretch of country than merely owning it. The explicit theme of a contemporary and precisely analogous design by Gainsborough's mentor Francis Hayman suggests that the people in such pictures were engaged in philosophic enjoyment of 'the great Principle ... the genuine Light of uncorrupted and un perverted Nature

The professor's argument is worth quoting because it is so striking an illustration of the disingenuousness that bedevils the subject of art history. Of course it is very possible that Mr and Mrs Andrews were engaged in the philosophic enjoyment of unperverted Nature. But this in no way precludes them from being at the same time proud landowners. In most cases the possession of private land was the precondition for such philosophic enjoyment - which was not uncommon among the landed gentry. Their enjoyment of ' uncorrupted and unperverted nature' did not, however, usually include the nature of other men. The sentence of poaching at that time was deportation. If a man stole a potato he risked a public whipping ordered by the magistrate who would be a landowner. There were very strict property limits to what was considered natural.

The point being made is that, among the pleasures their portrait gave to Mr and Mrs Andrews, was the pleasure of seeing themselves depicted as landowners and this pleasure was enhanced by the ability of oil paint to render their land in all its substantiality. And this is an observation which needs to be made, precisely because the cultural history we are normally taught pretends that it is an unworthy one.

Our survey of the European oil painting has been very brief and therefore very crude. It really amounts to no more than a project for study - to be undertaken perhaps by others. But the starting point of the project should be clear. The special qualities of oil painting lent themselves to a special system of conventions for representing the visible. The sum total of these conventions is the way of seeing invented by oil painting. It is usually said that the oil painting in its frame is like an imaginary window open on to the world. This is roughly the tradition's own image of itself - even allowing for all the stylistic changes (Mannerist, Baroque, Neo-Classic, Realist, etc.) which took place during four centuries. We are arguing that if one studies the culture of the European oil painting as a whole, and if one leaves aside its own claims for itself, its model is not so much a framed window open on to the world as a safe let into the wall, a safe in which the visible has been deposited.

We are accused of being obsessed by property. The truth is the other way round. It is the society and culture in question which is so obsessed. Yet to an obsessive his obsession always seems to be of the nature of things and so is not recognized for what it is. The relation between property and art in European culture appears natural to that culture, and consequently if somebody demonstrates the extent of the property interest in a given cultural field, it is said to be a demonstration of his obsession. And this allows the Cultural Establishment to project for a little longer its false rationalized image of itself.

The essential character of oil painting has been obscured by an almost universal misreading of the relationship between its 'tradition' and its 'masters'. Certain exceptional artists in exceptional circumstances broke free of the norms of the tradition and produced work that was diametrically opposed to its values; yet these artists are acclaimed as the tradition's supreme representatives: a claim which is made easier by the fact that after their death, the tradition closed around their work, incorporating minor technical innovations, and continuing as though nothing of principle had been disturbed. This is why Rembrandt or Vermeer or Poussin or Chardin or Goya or Turner had no followers but only superficial imitators.

From the tradition a kind of stereotype of 'the great artist' has emerged. This great artist is a man whose life-time is consumed by struggle: partly against material circumstances, partly against incomprehension, partly against himself. He is imagined as a kind of Jacob wrestling with an Angel. (The examples extend from Michelangelo to Van Gogh.) In no other culture has the artist been thought of in this way. Why then in this culture? We have already referred to the exigencies of the open art market. But the struggle was not only to live. Each time a painter realized that he was dissatisfied with the limited role of painting as a celebration of material property and of the status that accompanied it, he inevitably found himself struggling with the very language of his own art as understood by the tradition of his calling.

The two categories of exceptional works and average (typical) works are essential to our argument. But they cannot be applied mechanically as critical criteria. The critic must understand the terms of the antagonism. Every exceptional work was the result of a prolonged successful struggle. Innumerable works involved no struggle. There were also prolonged yet unsuccessful struggles.

To be an exception a painter whose vision had been formed by the tradition, and who had probably studied as an apprentice or student from the age of sixteen, needed to recognize his vision for what it was, and then to separate it from the usage for which it had been developed. Single-handed he had to contest the norms of the art that had formed him. He had to see himself as a painter in a way that denied the seeing of a painter. This meant that he saw himself doing something that nobody else could foresee. The degree of effort required is suggested in two self-portraits by Rembrandt.

The first was painted in 1634 when he was twenty-eight; the second thirty years later. But the difference between them amounts to something more than the fact that age has changed the painter's appearance and character.

The first painting occupies a special place in, as it were, the film of Rembrandt's life. He painted it in the year of his first marriage. In it he is showing off Saskia his bride. Within six years she will be dead. The painting is cited to sum up the so-called happy period of the artist's life. Yet if one approaches it now without sentimentality, one sees that its happiness is both formal and unfelt. Rembrandt is here using the traditional methods for their traditional purposes. His individual style may be becoming recognizable. But it is no more than the style of a new performer playing a traditional role. The painting as a whole remains an advertisement for the sitter's good fortune, prestige and wealth. (In this case Rembrandt's own.) And like all such advertisements it is heartless.

In the later painting he has turned the tradition against itself. He has wrested its language away from it. He is an old man. All has gone except a sense of the question of existence, of existence as a question. And the painter in him - who is both more and less than the old man - has found the means to express just that, using a medium which had been traditionally developed to exclude any such question.