7

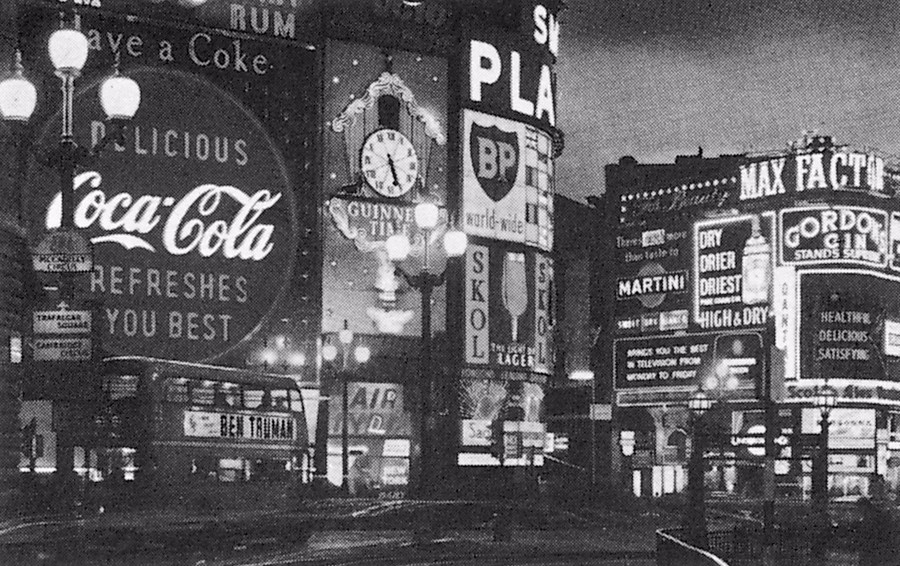

In the cities in which we live, all of us see hundreds of publicity images every day of our lives. No other kind of image confronts us so frequently.

In no other form of society in history has there been such a concentration of images, such a density of visual messages.

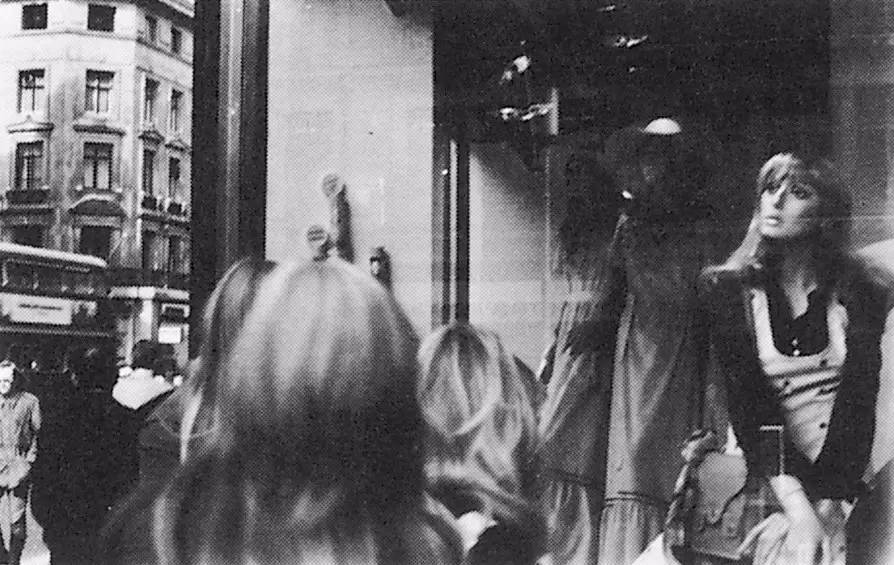

One may remember or forget these messages but briefly one takes them in, and for a moment they stimulate the imagination by way of either memory or expectation. The publicity image belongs to the moment. We see it as we turn a page, as we turn a corner, as a vehicle passes us. Or we see it on a television screen whilst waiting for the commercial break to end. Publicity images also belong to the moment in the sense that they must be continually renewed and made up-to-date. Yet they never speak of the present. Often they refer to the past and always they speak of the future.

We are now so accustomed to being addressed by these images that we scarcely notice their total impact. A person may notice a particular image or piece of information because it corresponds to some particular interest he has. But we accept the total system of publicity images as we accept an element of climate. For example, the fact that these images belong to the moment but speak of the future produces a strange effect which has become so familiar that we scarcely notice it. Usually it is we who pass the image - walking, travelling, turning a page; on the tv screen it is somewhat different but even then we are theoretically the active agent - we can look away, turn down the sound, make some coffee. Yet despite this, one has the impression that publicity images are continually passing us, like express trains on their way to some distant terminus. We are static; they are dynamic - until the newspaper is thrown away, the television programme continues or the poster is posted over.

Publicity is usually explained and justified as a competitive medium which ultimately benefits the public (the consumer) and the most efficient manufacturers - and thus the national economy. It is closely related to certain ideas about freedom: freedom of choice for the purchaser: freedom of enterprise for the manufacturer. The great hoardings and the publicity neons of the cities of capitalism are the immediate visible sign of 'The Free World'.

For many in Eastern Europe such images in the West sum up what they in the East lack. Publicity, it is thought, offers a free choice.

It is true that in publicity one brand of manufacture, one firm , competes with another; but it is also true that every publicity image confirms and enhances every other. Publicity is not merely an assembly of competing messages: it is a language in itself which is always being used to make the same general proposal. Within publicity, choices are offered between this cream and that cream, that car and this car, but publicity as a system only makes a single proposal.

It proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more. This more, it proposes, will make us in some way richer - even though we will be poorer by having spent our money.

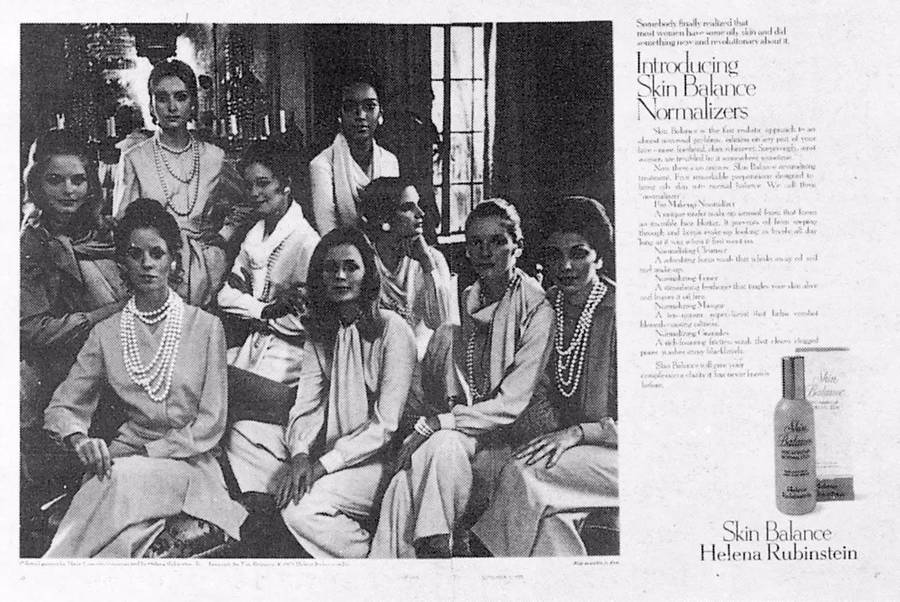

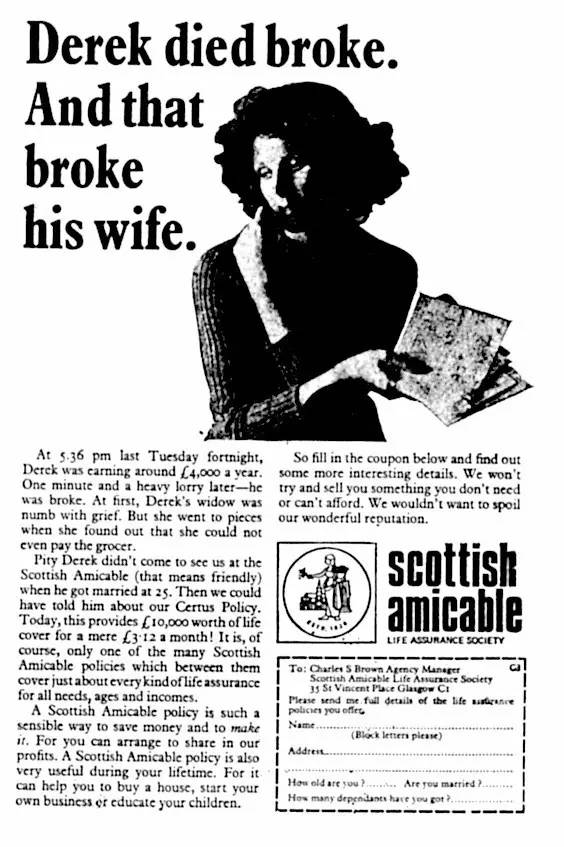

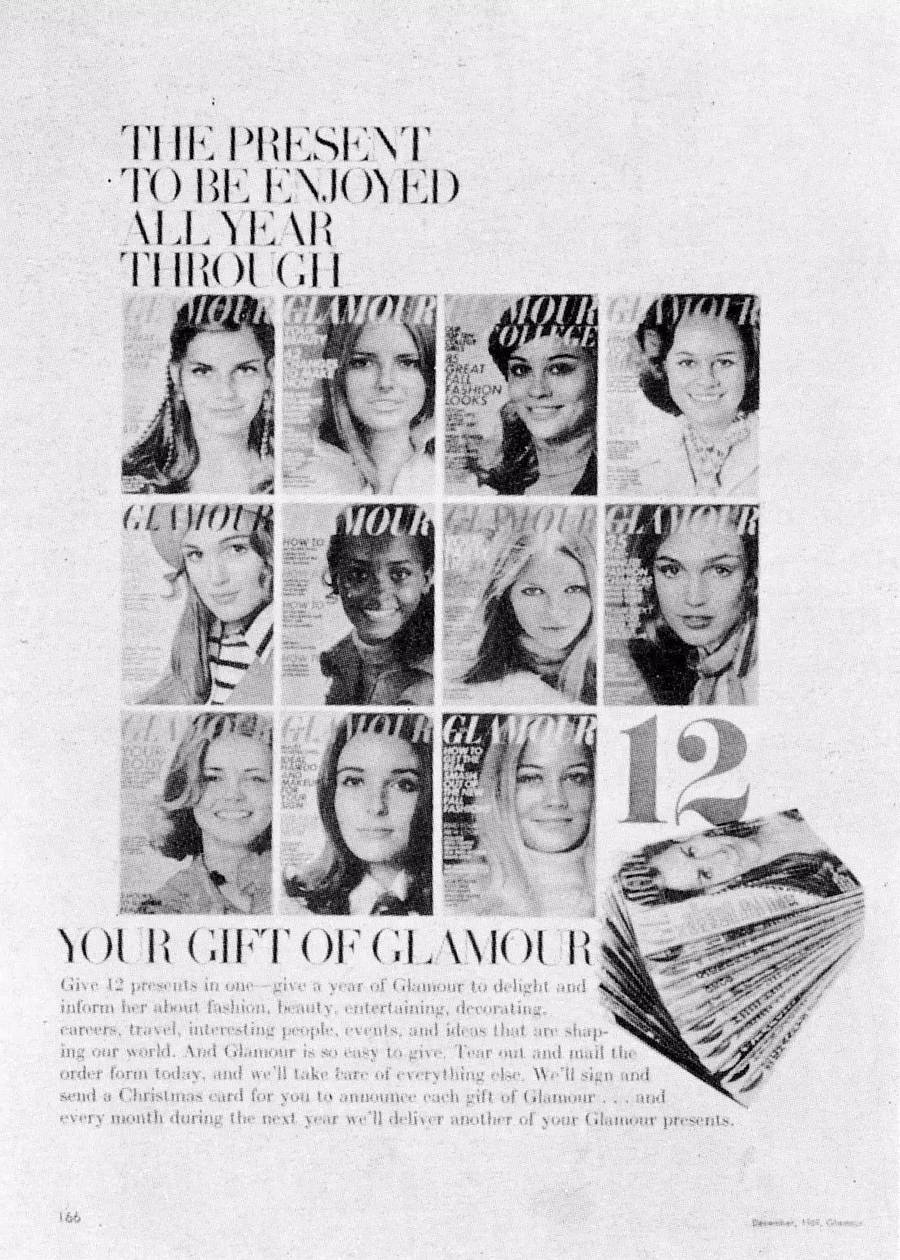

Publicity persuades us of such a transformation by showing us people who have apparently been transformed and are, as a result, enviable. The state of being envied is what constitutes glamour. And publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour.

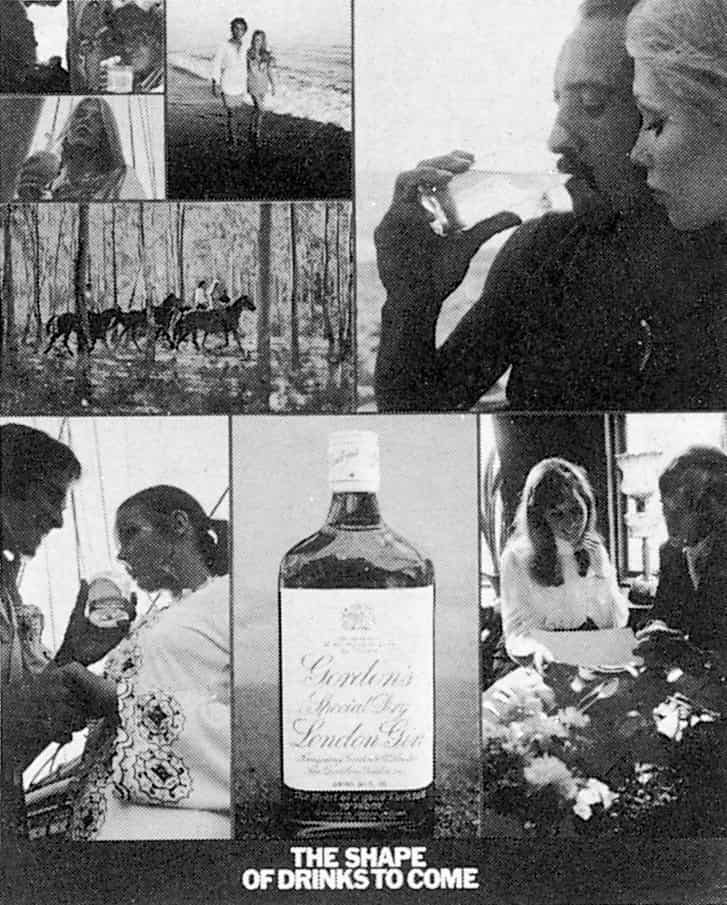

It is important here not to confuse publicity with the pleasure or benefits to be enjoyed from the things it advertises. Publicity is effective precisely because it feeds upon the real. Clothes, food, cars, cosmetics, baths, sunshine are real things to be enjoyed in themselves. Publicity begins by working on a natural appetite for pleasure. But it cannot offer the real object of pleasure and there is no convincing substitute for a pleasure in that pleasure's own term s. The more convincingly publicity conveys the pleasure of bathing in a warm , distant sea, the more the spectator-buyer will become aware that he is hundreds of miles away from that sea and the more remote the chance of bathing in it will seem to him. This is why publicity can never really afford to be about the product or opportunity it is proposing to the buyer who is not yet enjoying it. Publicity is never a celebration of a pleasure-in-itself. Publicity is always about the future buyer. It offers him an image of himself made glamorous by the product or opportunity it is trying to sell. The image then makes him envious of himself as he might be. Yet what makes this self-which-he-might-be enviable? The envy of others. Publicity is about social relations, not objects. Its promise is not of pleasure, but of happiness: happiness as judged from the outside by others. The happiness of being envied is glamour.

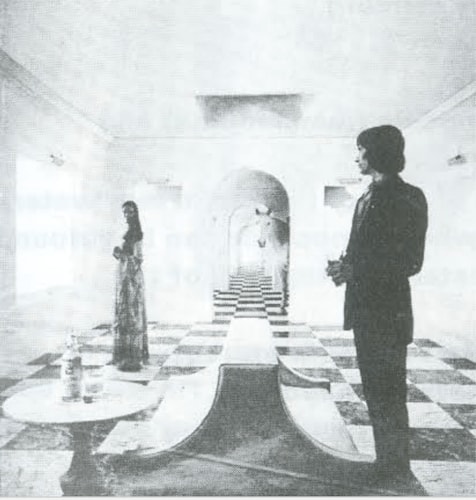

Being envied is a solitary form of reassurance. It depends precisely upon not sharing your experience with those who envy you. You are observed with interest but you do not observe with interest - if you do, you will become less enviable. In this respect the envied are like bureaucrats; the more impersonal they are, the greater the illusion (for themselves and for others) of their power. The power of the glamorous resides in their supposed happiness: the power of the bureaucrat in his supposed authority. It is this which explains the absent, unfocused look of so many glamour images. They look out over the looks of envy which sustain them.

The spectator-buyer is meant to envy herself as she will become if she buys the product. She is meant to imagine herself transformed by the product into an object of envy for others, an envy which will then justify her loving herself. One could put this another way: the publicity image steals her love of herself as she is, and offers it back to her for the price of the product.

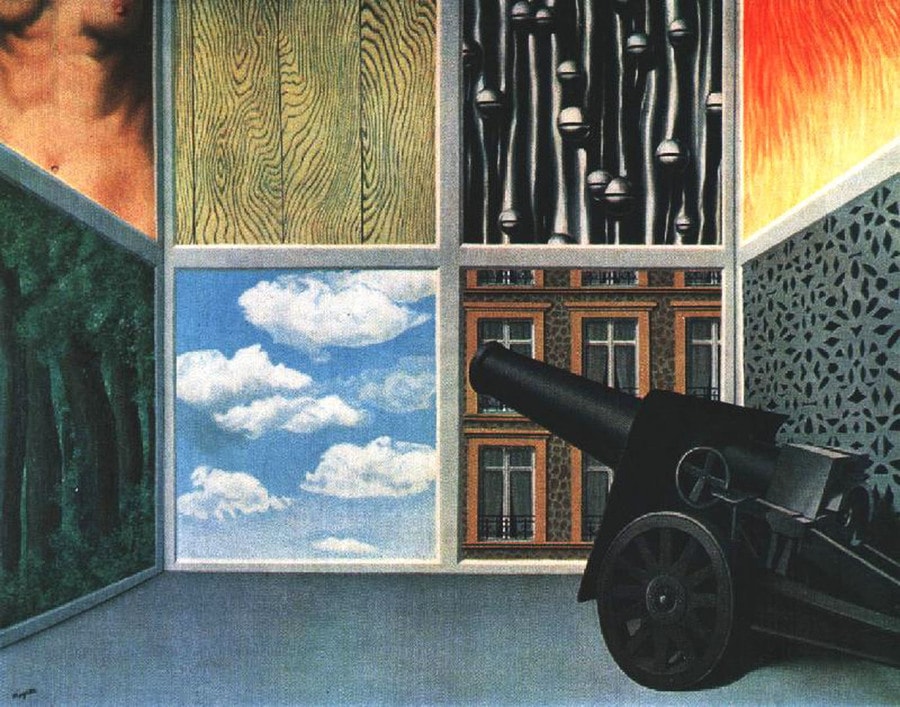

Does the language of publicity have anything in common with that of oil painting which, until the invention of the camera, dominated the European way of seeing during four centuries?

It is one of those questions which simply needs to be asked for the answer to become clear. There is a direct continuity. Only interests of cultural prestige have obscured it. At the same time, despite the continuity, there is a profound difference which it is no less important to examine.

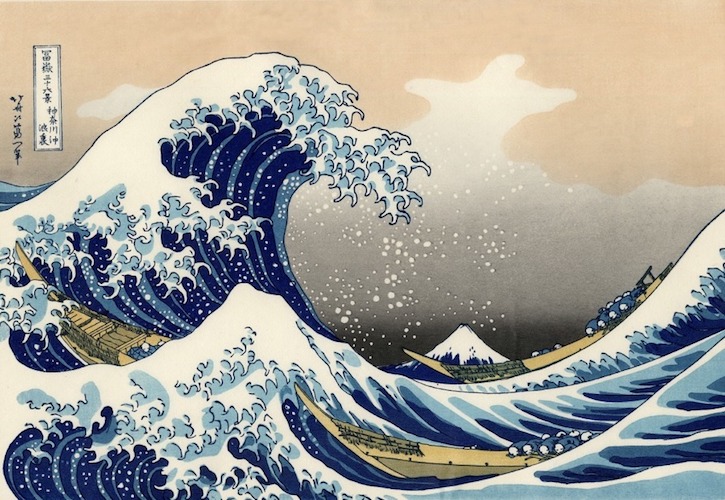

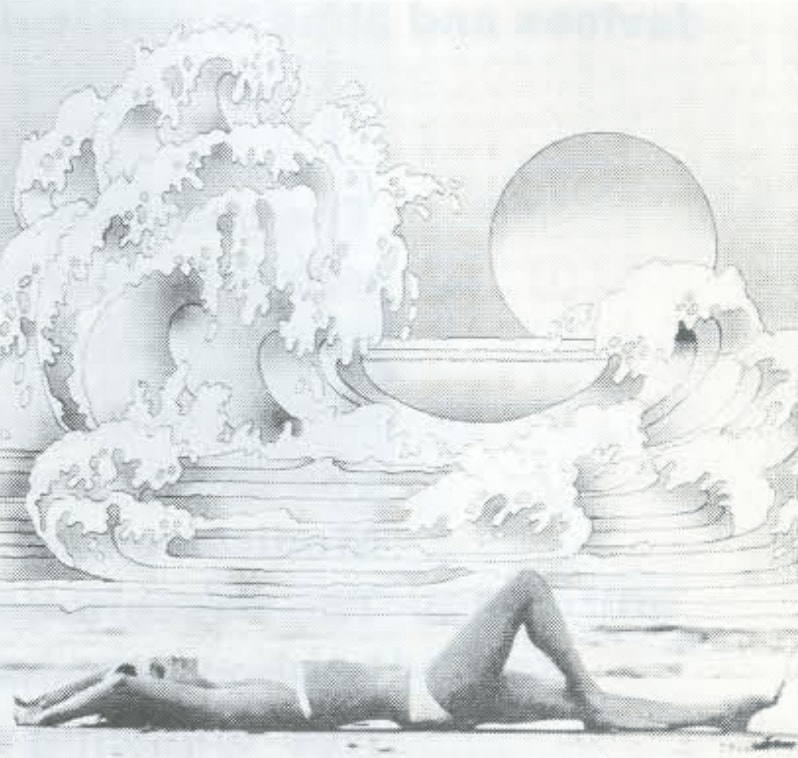

There are many direct references in publicity to works of art from the past. Sometimes a whole image is a frank pastiche of a well-known painting.

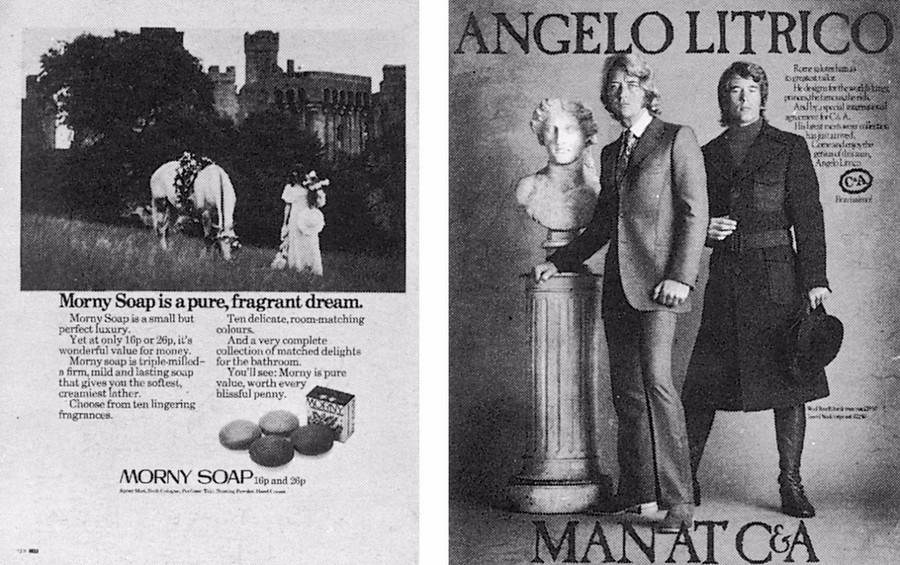

Publicity images often use sculptures or paintings to lend allure or authority to their own message. Framed oil paintings often hang in shop windows as part of their display.

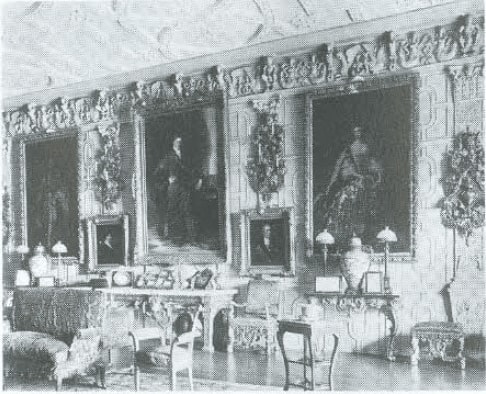

Any work of art 'quoted' by publicity serves two purposes. Art is a sign of affluence; it belongs to the good life; it is part of the furnishing which the world gives to the rich and the beautiful.

But a work of art also suggests a cultural authority, a form of dignity, even of wisdom , which is superior to any vulgar material interest; an oil painting belongs to the cultural heritage; it is a reminder of what it means to be a cultivated European. And so the quoted work of art (and this is why it is so useful to publicity) says two almost contradictory things at the same time: it denotes wealth and spirituality: it implies that the purchase being proposed is both a luxury and a cultural value. Publicity has in fact understood the tradition of the oil painting more thoroughly than most art historians. It has grasped the implications of the relationship between the work of art and its spectator-owner and with these it tries to persuade and flatter the spectator-buyer.

The continuity, however, between oil painting and publicity goes far deeper than the 'quoting' of specific paintings. Publicity relies to a very large extent on the language of oil painting. It speaks in the same voice about the same things. Sometimes the visual correspondences are so close that it is possible to play a game of 'Snap !' - putting almost identical images or details of images side by side.

It is not, however, just at the level of exact pictorial correspondence that the continuity is important: it is at the level of the sets of signs used.

Compare the images of publicity and paintings in this book, or take a picture magazine, or walk down a smart shopping street looking at the window displays, and then turn over the pages of an illustrated museum catalogue, and notice how similarly messages are conveyed by the two media. A systematic study needs to be made of this. Here we can do no more than indicate a few areas where the similarity of the devices and aims is particularly striking.

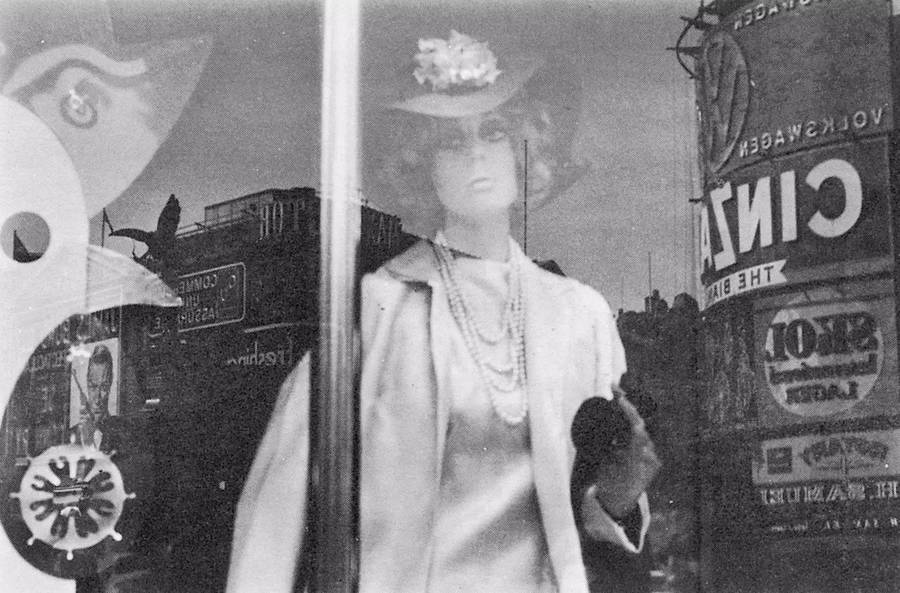

The gestures of models (mannequins) and mythological figures.

The romantic use of nature (leaves, trees, water) to create a place where innocence can be refound.

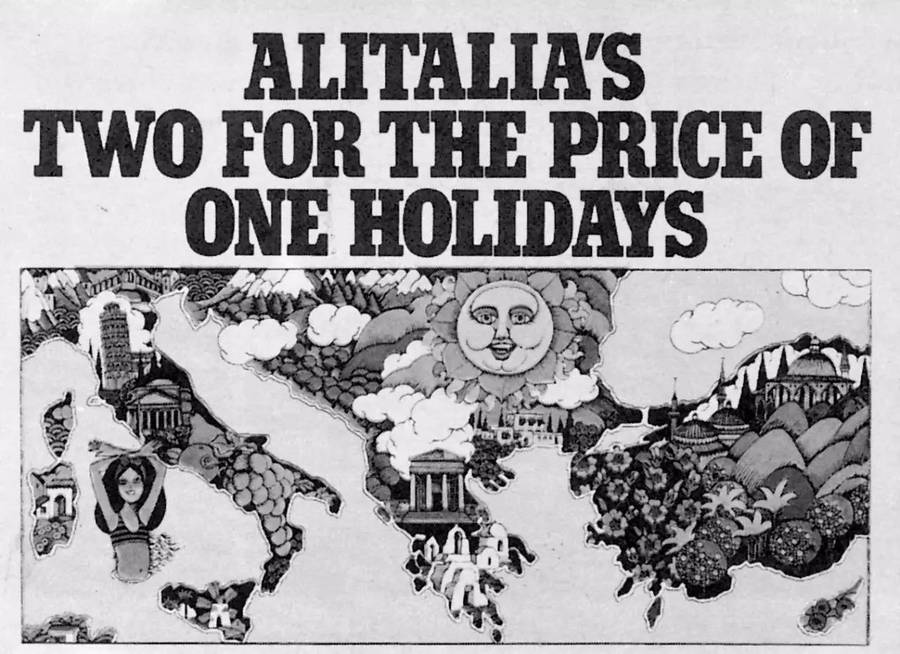

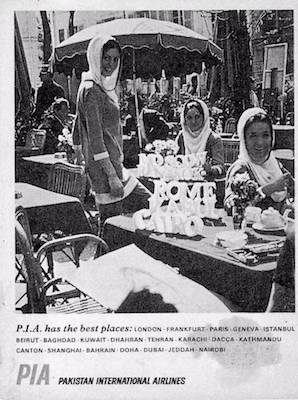

The exotic and nostalgic attraction of the Mediterranean.

The poses taken up to denote stereotypes of women: serene mother (madonna), free-wheeling secretary (actress, king's mistress), perfect hostess (spectator-owner's wife ), sex-object (Venus, nymph surprised), etc.

The special sexual emphasis given to women's legs.

The materials particularly used to indicate luxury: engraved metal, furs, polished leather, etc.

The gestures and embraces of lovers, arranged frontally for the benefit of the spectator.

The sea, offering a new life.

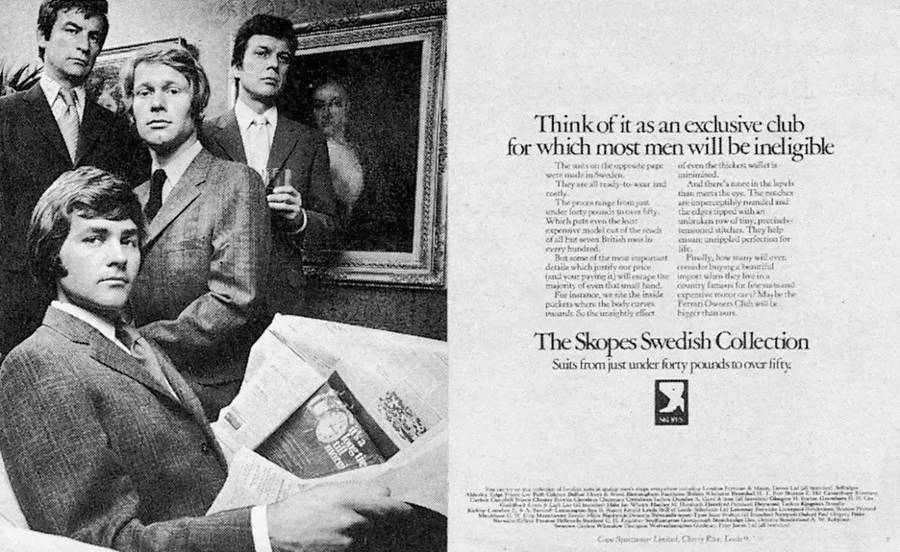

The physical stance of men conveying wealth and virility.

The treatment of distance by perspective - offering mystery.

The equation of drinking and success.

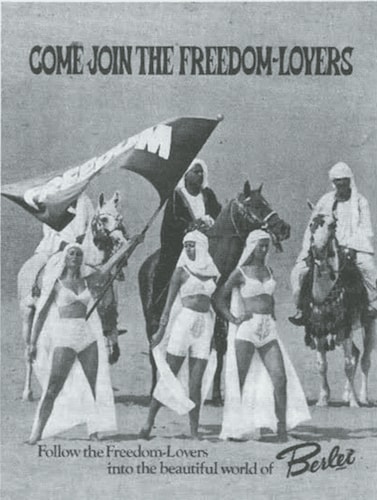

The man as knight (horseman) become motorist.

Why does publicity depend so heavily upon the visual language of oil painting?

Publicity is the culture of the consumer society. It propagates through images that society's belief in itself. There are several reasons why these images use the language of oil painting.

Oil painting, before it was anything else, was a celebration of private property. As an art-form it derived from the principle that you are what you have.

It is a mistake to think of publicity supplanting the visual art of post-Renaissance Europe; it is the last moribund form of that art.

Publicity is, in essence, nostalgic. It has to sell the past to the future. It cannot itself supply the standards of its own claims. And so all its references to quality are bound to be retrospective and traditional. It would lack both confidence and credibility if it used a strictly contemporary language.

Publicity needs to turn to its own advantage the traditional education of the average spectator-buyer. What he has learnt at school of history, mythology, poetry can be used in the manufacturing of glamour. Cigars can be sold in the name of a King, underwear in connection with the Sphinx, a new car by reference to the status of a country house.

In the language of oil painting these vague historical or poetic or moral references are always present. The fact that they are imprecise and ultimately meaningless is an advantage: they should not be understandable, they should merely be reminiscent of cultural lessons half-learnt. Publicity makes all history mythical, but to do so effectively it needs a visual language with historical dimensions.

Lastly, a technical development made it easy to translate the language of oil painting into publicity cliches. This was the invention, about fifteen years ago, of cheap colour photography. Such photography can reproduce the colour and texture and tangibility of objects as only oil paint had been able to do before. Colour photography is to the spectator-buyer what oil paint was to the spectator-owner.

Both media use similar, highly tactile means to play upon the spectator's sense of acquiring the real thing which the image shows. In both cases his feeling that he can almost touch what is in the image reminds him how he might or does possess the real thing.

Yet, despite this continuity of language, the function of publicity is very different from that of the oil Painting. The spectator-buyer stands in a very different relation to the world from the spectator-owner.

The oil painting showed what its owner was already enjoying among his possessions and his way of life. It consolidated his own sense of his own value. It enhanced his view of himself as he already was. It began with facts, the facts of his life. The paintings embellished the interior in which he actually lived.

The purpose of publicity is to make the spectator marginally dissatisfied with his present way of life. Not with the way of life of society, but with his own within it. It suggests that if he buys what it is offering, his life will become better. It offers him an improved alternative to what he is.

The oil painting was addressed to those who made money out of the market. Publicity is addressed to those who constitute the market, to the spectator-buyer who is also the consumer-producer from whom profits are made twice over - as worker and then as buyer. The only places relatively free of publicity are the quarters of the very rich; their money is theirs to keep.

Alternatively the anxiety on which publicity plays is the fear that having nothing you will be nothing.

Money is life. Not in the sense that without money you starve. Not in the sense that capital gives one class power over the entire lives of another class. But in the sense that money is the token of, and the key to, every human capacity. The power to spend money is the power to live. According to the legends of publicity, those who lack the power to spend money become literally faceless. Those who have the power become lovable.

Publicity speaks in the future tense and yet the achievement of this future is endlessly deferred. How then does publicity remain credible - or credible enough to exert the influence it does? It remains credible because the truthfulness of publicity is judged, not by the real fulfilment of its promises, but by the relevance of its fantasies to those of the spectator-buyer. Its essential application is not to reality but to daydreams.

To understand this better we must go back to the notion of glamour.

Glamour is a modern invention. In the heyday of the oil painting it did not exist. Ideas of grace, elegance, authority amounted to something apparently similar but fundamentally different.

Mrs Siddons as seen by Gainsborough is not glamorous, because she is not presented as enviable and therefore happy. She may be seen as wealthy, beautiful, talented, lucky. But her qualities are her own and have been recognized as such. What she is does not entirely depend upon others wanting to be like her. She is not purely the creature of others' envy - which is how, for example, Andy Warhol presents Marilyn Monroe.

The entire world becomes a setting for the fulfilment of publicity's promise of the good life. The world smiles at us. It offers itself to us. And because everywhere is imagined as offering itself to us, everywhere is more or less the same.

According to publicity to be sophisticated is to live beyond conflict.

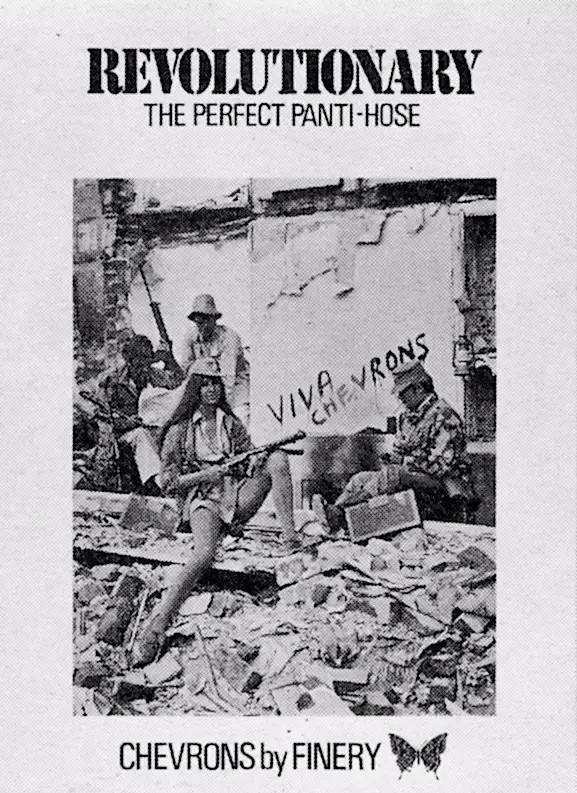

Publicity can translate even revolution into its own terms.

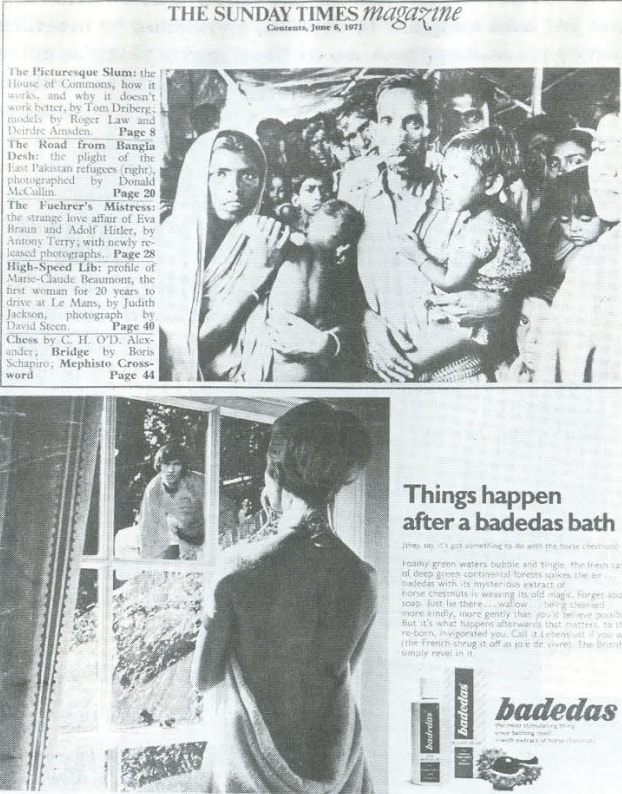

The contrast between publicity's interpretation of the world and the world's actual condition is a very stark one, and this sometimes becomes evident in the colour magazines which deal with news stories. Overleaf is the contents page of such a magazine.

The shock of such contrasts is considerable: not only because of the coexistence of the two worlds shown, but also because of the cynicism of the culture which shows them one above the other. It can be argued that the juxtaposition of images was not planned. Nevertheless the text, the photographs taken in Pakistan, the photographs taken for the advertisements, the editing of the magazine, the layout of the publicity, the printing of both, the fact that advertiser's pages and news pages cannot be co-ordinated - all these are produced by the same culture.

It is not, however, the moral shock of the contrast which needs emphasizing. Advertisers themselves can take account of the shock. The Advertisers Weekly (3 March 1972) reports that some publicity firm s, now aware of the commercial danger of such unfortunate juxtapositions in news magazines, are deciding to use less brash, more sombre images, often in black and white rather than colour. What we need to realize is what such contrasts reveal about the nature of publicity.

Publicity is essentially eventless. It extends just as far as nothing else is happening. For publicity all real events are exceptional and happen only to strangers. In the Bangla Desh photographs, the events were tragic and distant. But the contrast would have been no less stark if they had been events near at hand in Derry or Birmingham. Nor is the contrast necessarily dependent upon the events being tragic. If they are tragic, their tragedy alerts our moral sense to the contrast. Yet if the events were joyous and if they were photographed in a direct and unstereotyped way the contrast would be just as great.

Publicity, situated in a future continually deferred, excludes the present and so eliminates all becoming, all development. Experience is impossible within it. All that happens, happens outside it.

The fact that publicity is eventless would be immediately obvious if it did not use a language which makes of tangibility an event in itself. Everything publicity shows is there awaiting acquisition. The act of acquiring has taken the place of all other actions, the sense of having has obliterated all other senses.

Publicity exerts an enormous influence and is a political phenomenon of great importance. But its offer is as narrow as its references are wide. It recognizes nothing except the power to acquire. All other human faculties or needs are made subsidiary to this power. All hopes are gathered together, made homogeneous, simplified, so that they become the intense yet vague, magical yet repeatable promise offered in every purchase. No other kind of hope or satisfaction or pleasure can any longer be envisaged within the culture of capitalism.

Publicity is the life of this culture - in so far as without publicity capitalism could not survive - and at the same time publicity is its dream.

Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their own interests as narrowly as possible. This was once achieved by extensive deprivation. Today in the developed countries it is being achieved by imposing a false standard of what is and what is not desirable.